Scienceblogs has recently accumulated some of my favorite stops in the blogosphere into one convenient portal, and introduced me to a few more well worth reading, such as Uncertain Principles. A recent post (and growing comments thread) discusses irritating misconceptions in science. Maybe it's the fact that I'm marking exams at the moment and it's put me in a bad mood, but once I started, I couldn't stop thinking of geological examples. Here's my list, in no particular order of non-preference.

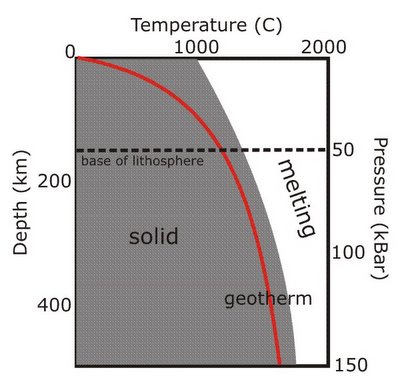

Tectonic plates move around on top of a sea of molten lava. Many people mistakenly believe that the beneath the Earth's crust lies a seething mass of molten lava, ready to erupt at any minute. Not true. As the figure below shows, although the temperature of a rock does increase with depth (as shown by the red line, the geotherm), so does its melting point due to the immense pressure exerted by tens of km of rock piled on top of it.

As you can see, at no point does the geotherm cross the solidus (the temperature at which melting would start), so the rocks remain solid even at great depths. However, below about 150-200km, the geotherm gets quite close to the melting point, which allows rocks to more easily deform and flow (a process known as creep). Think less molten lava, more Silly Putty. Mantle convection can therefore occur below this depth, even though the rocks are not melted. The more rigid, non convecting rocks above this boundary form the lithosphere, which forms the major part of tectonic plates (the crust is just a skin on top).

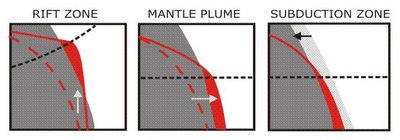

Melting to form magma, and hence volcanism, only occurs when something happens to disrupt this situation; three common ways that this happens are shown below. The geotherm can cross the solidus by being shifted upwards by rifting (which thins the lithosphere and allows upwelling of hotter mantle to shallower depths), or across by a mantle plume (an upwelling of hotter material from deeper within the Earth). The melting point of the mantle rocks can also be reduced by a change in composition; at subduction zones, this is caused by the addition of water from the downgoing plate.

This is the reason why volcanoes only occur in particular geological environments on the Earth's surface, rather than everywhere.

What earthquake and volcano 'prediction' actually means. Sorry folks, but it's never going to get to the stage where we can point to a particular volcano or fault and say, "this will erupt/rupture next Thursday at 11:00". For both volcanoes and faults, geologists can try and reconstruct the past history of eruptions and earthquakes, to see how regularly they happen. They can also watch for signs of imminent activity: the filling of a volcano's magma chamber might be accompanied by small earthquakes and ground uplift; the build-up of strain across a fault can be monitored by GPS. This gives some clues as the the liklihood of something happening, but it's just that - a probability, not a certainty. So the most precise forecast you're ever going to get is, "there's a high (or low) likilihood of rupture/eruption in the immediate future". And, particularly for earthquakes, "immediate future" could well mean "in the next decade or two"...

There is one 'geological column' for the whole Earth. The geological timescale divides the 4.5 billion years of earth history into distinct chunks, based on changes in environment or dominant forms of life over time. However, this does not mean that every rock of a particular age is the same. Just like today, in these periods many different processes were leaving their own unique record; marine deposits formed in shallow seas, deltas built out from coastlines, deserts formed vast dune fields. In other places, uplift of ancient mountain ranges led to no deposition, and erosion of rocks that had been laid down in earlier times. So there is no one geological column; each area has its own unique sequence of rock types, often with large time gaps in between different units. Correlating them all with each other is one of the major tasks of the geologist.

All radiometric dating is 'carbon dating'. This has cropped up in the exams I'm currently marking - I'm assuming (fervently hoping!) that it's not due to anything I said in the lectures, and it just reflects the generally held notion that all radiometric dating involves 14C. It's the isotope most people have heard of, because it is so widely used in archaeology. However, trying to 'carbon date' rocks is generally pointless; 14C has a half-life of 5,730 years, which means after about 50,000 years it has virtually all gone. Assuming there was anything to begin with, of course; there's not generally much carbon in volcanic rocks. This doesn't matter, because there's a whole array of different isotopes with half-lives much better suited to dating rocks tens of millions of years old.

Blowing up Earth-bound comets and asteroids at the last minute will save the day.. Nope, we'd still be doomed (OK, this is tenuous geologically, but it does annoy me).

A geologist can tell you the life story of a random pebble you've picked up on the beach. Don't get me wrong, pebbles can be useful - they tell you about local rock types along that section of coast, for one thing, which is very handy when you're mapping. Just don't be disappointed when the most information you get from me is 'sandstone'.

Well, that's the list so far...additions are welcomed.

02 February, 2006

Annoying misconceptions in Geology

Posted by

Chris R

at

5:50 pm

![]()

Labels: daft science, earthquakes, geology, volcanoes

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Hi,

What is it that makes earthquake predictions so difficult in principle - I can imagine complexity would pretty much destroy any attempt at accuracy. But, is it governed some chaotic dynamics or something which makes things a bit worse ?

By the way thank you for the great article ! I am a physics student with a general interest in sciences. And I find it pretty difficult to find people who blog about geological sciences as compared to life-sciences or physical sciences. So, I am very happy to come across a geology blog ! I hope you don't mind me adding you to my list of links..

You're pretty much right. The rupture process in an earthquake appears to be chaotic - large changes in outcome are caused by tiny variations in the initial conditions. Sometimes when a small section of the fault fails, the rupture remains very localised and you get a small earthquake, only detectable by instruments; sometimes that small rupture will trigger failure over a much larger section of the fault and cause a big earthquake. So although you can easily measure when a lot of strain has built up across a fault, predicting which of the many tiny earthquakes, that happen all the time, is going to turn into the big one which releases it all is probably impossible.

There's what looks like a good discussion of the ins and outs of earthquake prediction here.

Glad you like my efforts. One of the things motivating me is the lack of geological bloggers out there. Let me know if you find any more!

Hi! I really like your blog and specially this article. I'm a geology student from Peru and I have to say that there's one thing that annoys me. I don't know if it's just here, but there seems to be 2 groups of people: one that gets scared after a couple regular M4+ earthquakes because they think a big earthquake is going to come, and the other that thinks that since there are a couple regular earthquakes in a row the chances of a bigger one are less because energy is "dissipating". People just don't get that one event may not be related to another and if they are sometimes one is an aftershock of the other, and many other reasons. Those assumptions make me mad sometimes, and you can even hear them in the news... I think that if people cared enough to learn at least some basic geology, many lives could be saved.

About your last comment, I've got to say I agree with you that there aren't enough geological bloggers, let alone spanish speaking ones. That's exactly the reason why I decided to start my own blog almost a month ago. It's in spanish of course and geology is my main subject but it's not the only one. And although my insight is just the one of a 4th year geology student I do what I can. Check it out if you have time http://migeo.blogspot.com, comments accepted.

Anyway, nice to meet you... and read you. Take care and keep on posting.

Post a Comment