I’ve just spent a week hiking in the Vanoise National Park; we did a five day loop around the main glacial massif. On the whole, it was a thoroughly enjoyable experience; after an unpromising start the weather was fabulous, the scenery fantastic (I took an old film camera so no photos to show off as yet) and I had the unforgettable experience of a golden eagle flying 10 feet above my head, close enough to pick out individual feathers on his underbelly. I’m glad I didn’t look like lunch, although his long stare indicated he was thinking about it.

The hike was no without it’s challenges, however, and the second day was particularly hard work. On paper, it was difficult enough; 1200 m of ascent, including a stiff climb to 2916 m to get across the Col d’Aussois. In reality, we proceeded to make it even tougher for ourselves by getting un peu perdu. As we approached the Col, we lost the trail, but we could see a track going up the hillside across the river and decided that must be the route. We persevered with this belief even after we discovered that the bridge promised in our guidebook had apparently vanished; it was only when we’d spent an hour struggling up it - and reached a much lower col on the wrong side of some rather hefty mountains – that we realised that we’d gone a bit wrong. When we looked back into the valley, we could see the actual track, heading upwards into the next valley. Merde.

Fortunately, our elevated perspective also showed us that we didn’t have to completely retrace our steps, an option almost as unpalatable as heading on and trying to find another route across the ridge; instead, we just had to descend enough to contour around into the next valley, and then re-ascend to rejoin the trail up to the Col d’Aussois after it crossed the river (on a very existent bridge). Despite this short cut we lost almost two hours, and fretting over time combined with tiredness from our abortive first ascent, the altitude, and an unrelentingly steep path to make the ascent to the top of the proper col one of the toughest things I’ve done in quite a while. My world contracted in on itself; the track was reasonably well marked by cairns, and rather than focussing on the distance to the summit, my mind was fixated on driving myself onward to the next cairn, and then the next one, and then the next one… all the time my breath was getting shorter, my rucksack was getting apparently heavier, and lifting my feet was becoming ever more difficult. And then, just when I thought I’d reached the top, I struggled over the break in slope to discover yet more up. By this stage, it’s only slightly melodramatic to claim that the point of the ascent was only a dim recollection in the back of my mind; pretty much the only thought in my head was, “I’m not going to let this bloody hill beat me!”

By 7.30, we’d all got to the top. Unfortunately, that was not the end; we now had to descend down to the refuge on the other side of the col. Down was good (although gravity can be a fickle friend when you’re knackered), but we had the small problem of about 90 minutes’ walking and half an hour of daylight left to do it in. Fortunately, thanks to one of my companion’s inspired twilight route-finding, we only needed our torches for the last 20 minutes, but even so we almost overshot our destination.

In the end, what should have been an eight hour trek had taken almost 12. However, although negotiating mountain trails in the dark is hardly recommended, we were never really in serious trouble; as a tale of danger and fortitude, this is hardly Touching the Void territory. However, looking back as the hike continued, I found myself thinking back to a post I started writing a few weeks back, discussing the vast gulf between the public perception of science and the process of actually doing science*, and I couldn’t help drawing parallels between that the physical ordeal of that day and the mental struggle of a PhD, or any research project. You start at the bottom of a big hill, and despite previous research as a guide the way forward is not clear (especially if you don’t find the key publication, as we neglected to properly consult the map). When a route does present itself, it may not be the correct one, and it may take you considerable time and effort to discover this. Your wrong paths may not be a complete dead end; a negative result can still constrain the problem, or (as happened during my PhD), the result which undermines a key assumption may finally reveal the true path to understanding. It’s disturbingly easy to get so lost in the day-to-day grind of generating and processing data, that you almost lose sight of the reasons you were interested in the first place. Just when you think you’ve got there, you discover a new complication with your data. And, of course, it takes much longer than it was supposed to.

If I really wanted to get lost in the metaphor, I could run with the whole “standing on the shoulders of giants” angle by musing that the hard day’s climbing gave us access to some spectacular mountain scenery in the following days. That, however, is somewhat immaterial to my point. I’ve often thought that a shortcoming of most science reporting, centred as it is around (if we’re lucky, informed) regurgitation of Nature press releases, is that it is exclusively concerned with the outcomes: the exciting results and nifty new hypotheses. Results are important, of course, but I sometimes think that focussing only on the final part of the scientific process means that many people do not realise exactly how many years’ graft has gone into attracting the public attention for that fleeting second (if it ever does). A scientist’s week does not consist of thinking up a nifty idea on Monday, running down to the lab and testing it on Tuesday and Wednesday, writing it up on Thursday and getting the plaudits on Friday. The view is great from the top - but it takes a whole lot of climbing to get there.

*Yes, I was thinking about blogging. But a nice walk has always provided good thinking time for me, so it’s not quite as sad as it might appear. Honest.

27 September, 2006

Mountain musings 1: The hard climb of science

Posted by

Chris R

at

11:15 pm

0

comments

![]()

Labels: academic life, climatology, geology

16 September, 2006

Gone roamin'

It's been a busy few days, as I've been trying to get stuff finished before I head off to do some walking in the French Alps. Lets hope the weather smiles on me.

Those needing their fix of top-notch writing can do worse than head over to the first edition of Philosophia Naturalis, the long-awaited physical sciences carnival now up over at Science and Reason. Tell them I sent you.

Posted by

Chris R

at

6:39 am

0

comments

![]()

13 September, 2006

The curse of the nerd

There’s a lot of posturing at the moment over at Scienceblogs (follow the links here, for example) over who is the nerdiest of them all. In some ways, this is an encouraging affirmation of the universal characteristics of human nature. Change a few key terms, ‘slide rule’ to ‘alloys’, for example and you could be in the streets of Essex listening to teenagers showing off their latest set of wheels. We just can’t resist the urge to shout about what hot stuff we are, even if the requirements within different social groups are somewhat different.

Over at Cosmic Variance, where Sean has an interesting take on the whole exercise:

I’m all in favor of celebrating nerdliness. But for me it’s very much a part of what should be a general appreciation for intellectual endeavor, whether technically oriented or not. And as a matter of personal experience, I’ve found science and engineering types to be at least as anti-intellectual as the average person on the street, when it comes to non-technical kinds of scholarship.

What is worse, there’s a certain point of view… that actually celebrates social awkwardness for its own sake... And that’s just wrong. I’m not talking about principled eccentricity, letting your freak flag fly — nothing wrong with that, in fact it’s admirable in its own way. Nor am I saying that everyone should be scouring the latest issues of GQ and Vogue for fashion tips; superficiality is just as bad as nerdliness. And laughing at our high-school (and college) selves is always fun and healthy. All I’m saying is that there is much to be valued in an ability to relate to other kinds of people in a disparate set of circumstances, take care of your appearance, and function effectively in a wider social context. These are skills we should try to cultivate, not disparage.

How true. One of the more unpleasant aspects of working in academia is that bullying, petulance and general obnoxiousness is an accepted (or, at best, tolerated) way of progressing in your field. In my department, I find myself in the odd and entirely undeserved position of being at the high end of the social skills spectrum, which even my best friends in the real world would tell you is a little frightening.

But why is this? I think this actually does link back to the somewhat negative stereotypes at large in general society: scientists as bumbling, socially inept and desperately uncool loners; science students as all of the above with added spots, crooked teeth and thick glasses. This is not an image your average teenager, highly susceptible to the ebb and flow of peer approval, wants associated with them, thanks very much. Hence even if there is a genuine interest, many do not persist in science (or, more accurately, put in enough work to leave the option open). Those who do are either comfortable enough with themselves to follow their interests despite peer pressure, or lack the social awareness to perceive or care about it*. I would submit that the latter group is by far the larger.

So it’s all a bit circular really – through this process of self-selection, those on the path towards a scientific or technical career are on average more socially inept than the general population. Within the group poor social skills are the norm, so they persist, reinforcing the general cultural stereotype and keeping scientists 'uncool'. Additionally, within the group there is also a backlash against other parts of culture, seemingly the preserve of people who look down on the science geek; hence the apparently contradictory anti-intellectualism that Sean notes. Breaking that circle is not an easy thing.

*Or you're such a well-known swot that you can choose to do what you like, in the certain knowledge that nothing you do will change people's perceptions of you.

Posted by

Chris R

at

10:43 pm

0

comments

![]()

11 September, 2006

Waking up

I must have been one of the last people to fly in that innocent age when thoughts of disaster tended more towards mechanical failure than being used as a missile. Early on the morning (UK time) of 11th September 2001, my long-haul flight from Singapore was flying in over the centre of London to land at Heathrow. I had just spent the summer travelling around the world as a post-graduation present to myself. I arrived back home in the early afternoon, and switched on the TV. I can't swear that my memories have not been melodramatised over time, but this was at about the time that the second plane hit the World Trade Centre. The next few hours seem unreal even now, with my jet-lagged brain recoiling from the sheer nightmarish horror of what unfolded.

Cut to five years later, and in a very real sense the dust from that day has yet to settle. Like many others, I'm not sure I'm liking the shapes of the new world which are starting to poke through the haze, partly a result of our leaders' delusion that you can declare war on, and beat, a noun (and an illegitimate proper noun to boot - I know what 'terror' is, but 'Terror'?). But given that more than enough is being written about the (mis)deeds of Bush and Blair, I find myself instead wanting to consider a slightly different notion: the idea of 9/11 as a 'wake-up call'. I am wondering, what exactly should it have woken us up to?

The obvious answer is the one our leaders give, and our media amplify: that there are scary people out there who want nothing less than the destruction of our entire way of life, and are willing to murder thousands of innocents to achieve it. This is true, but amoral sociopaths existed before five years ago. A more chilling realisation is the fact that in certain parts of the world, these peoples enjoy an alarming degree of support in the general populace, to the extent that the attacks on New York and the Pentagon were, and are, celebrated as the acts of heroic martyrs. That is dwelt upon, but perhaps less than it should, because it is a step on the slippery slope to thinking about the causes of that hatred.

I should probably add at this point that I utterly deplore any act which deliberately leads to the loss of innocent life - to discuss the causes of something is not to condone it. However, the necessity of that disclaimer is telling; it says that we are uncomfortable with questioning our unpopularity in the Middle East, and elsewhere. We would prefer to think of it as unreasoning and baseless. We're the good guys, surely? Our societies are free and tolerant and peaceful. No one could have any rational reason to hate us.

Unfortunately, our ignorance does not mean that such reasons do not exist. The advantages of liberal democracy, our freedom to live our lives the way we see fit, relatively free from disease and poverty, do not come without costs. The problem is that in our increasingly connected world, we are increasingly able to export those costs to the fringes. We have laws regulating working hours and the minimum wage, but we buy cheap clothes and trainers from countries that do not. Our supermarkets stock affordable fruit and vegetables imported from all corners of the earth, but those that grow it are not always given a fair price. Much of our meddling in the Middle East is linked to our need to secure cheap energy.

It is easy to ignore what we are not forced to see. We are vaguely aware of these issues, but being insulated from them we see the postive aspects of our society much more clearly. To those on the outside, however, where the negatives can impinge much more directly on peoples' daily lives, it is no suprise that their views are somewhat more ambivalent. If they feel that they are suffering to support our priviliged lifestyles, and if our immigration controls and trade protectionism appear to be preventing them from joining the party, then it is only a small step to the conviction that it is all intentional, that we are out to destroy them. And you can always find people - fanatics, power-hungry manipulators, weak despots - willing to help others make that step. Perhaps what we should have woken up to five years ago is that we have helped, however inadvertantly to make it a disturbingly small step for a disturbingly large number of people. Instead, by buying wholeheartedly into the 'Us versus Them' framing of Al-Quada, we have if anything made that step even smaller.

Posted by

Chris R

at

11:45 pm

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ranting

04 September, 2006

Lego Weapons of Mass Destruction

Remind yourself of the awesomeness of LEGO. Coincidentally, I'm moving flat at the moment and the junk under my bed includes a shoebox-full of the stuff. The urge to play is strong...

Via Kevin Beck.

Posted by

Chris R

at

4:27 pm

0

comments

![]()

01 September, 2006

The long road to ozone hole recovery

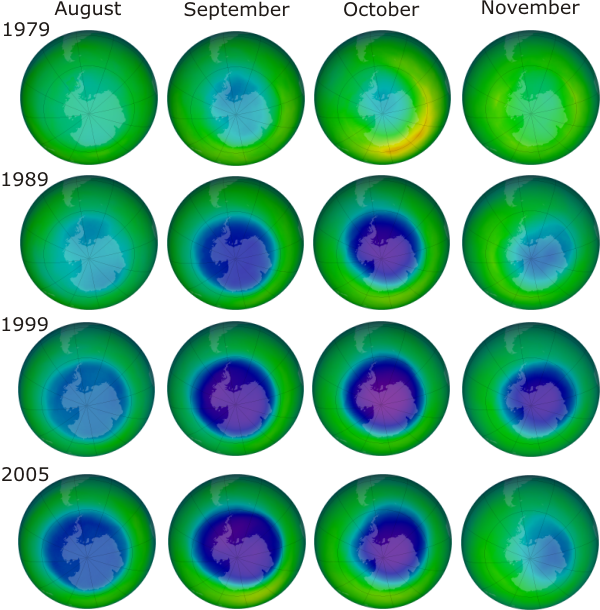

I'm somewhat late commenting on the story that the Antarctic ozone hole appears to have stopped growing, but I put together this figure last week by pulling images off the NASA Ozone Hole Watch website (click here for the latest image from this year), and it seems a shame to waste it. It depicts how the springtime concentration of ozone over the south pole has varied since 1979. Blue and purple indicate low ozone concentrations, green and yellow high concentrations.

This figure provides a qualitative impression - that the area of ozone depletion in the 2005 season was not enormously bigger or deeper than in 1999, and in fact appeared to recover a little earlier. This impression is confirmed by the more rigorous (but less pretty) figure below, which shows the annual variation in the size of the ozone hole since 1979 - click on it for the original (and clearer) version at this NASA site, where you can also see how the severity of ozone depletion has varied.

So it seems that in fact things have been stabilising for a while now - the sudden media interest can be traced to a NOAA press release to mark the 20 year anniversary of the study that confirmed that chlorine, released when CFCs are broken down by ultraviolet radiation, was the cause of ozone depletion above Antarctica. This work combined with a rare outbreak of non-partisan international cooperation to produce the Montreal Protocol. Even more remarkably, the agreement was actually pretty effective at curtailing the production of CFCs and other ozone-damaging chemicals:

(source)

However, the important thing to notice is that the thinning of the ozone layer above Antartica continued throughout the 1990s; although we cut the production of ozone-destroying chemicals, the molecules of those we have already released are persistant beasties, surviving in the atmosphere for anything up to 100 years. Indeed, as the graph here shows, the atmospheric concentration of flourocarbons has merely stablised in the last decade. Until it begins to fall, springtime ozone depletion above the Antarctic will continue (the latest research estimates full recovery in about 2065). The fact that our atmosphere is still suffering the consequences of CFC emitted two decades ago is a warning about the consequences of the other changes we have wrought on atmospheric chemisty. Even if we can agree to seriously cut the emission of greenhouse gases in the next decade or two, the full effect of what we've already emitted, and are currently emitting, will not play out for a long time afterwards (especially since climate change affects the ocean, which responds over timescales of centuries, not decades). More people need to realise that emissions cuts will not put the brakes on climate change; it is more akin to taking your foot off the accelerator.

Posted by

Chris R

at

2:50 pm

1 comments

![]()

Labels: climatology, environment