I’ve been puzzling over why what is a legitimate dispute between members of the pro-science camp, over emphasis and tone in the struggle against the forces of ignorance, always seems to break down into what could charitably be referred to as ‘arguing past each other’ (I’m not implying the coturnix is an offender here, by the way – he’s just got the best link summary).

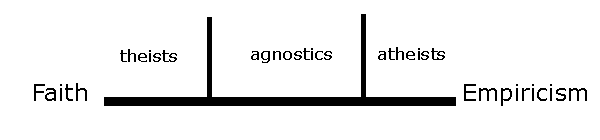

A common framing of different theological positions is to represent the continuum from theism through agnosticism to atheism as a change in the relative importance of empiricism and faith in a particular person’s worldview. An atheist places a high value on tangible evidence; a theist is more concerned with the greater truths that they feel exist outside of the world we can subject to experimental verification.

I can see some fairly obvious flaws with this representation. Committed empiricists see all the theists, fundamentalist and moderate, lumped together at the far end of the spectrum, which can make them highly suspicious of someone like Ken Miller, who is clearly a man of deep religious conviction even though he just as clearly values science. Furthermore, as we’ve been so recently reminded, at that empirical end of the spectrum you find people who have little time for faith themselves but will tolerate it in others (provided that religious views are not being foisted too egreriously on the unwilling) jostling for space for people who argue that all faith is silly and even dangerous. The fact that a single axis does not usefully capture the range of viewpoints and how they relate to each other seems to make it all too easy to misunderstand other peoples’ positions.

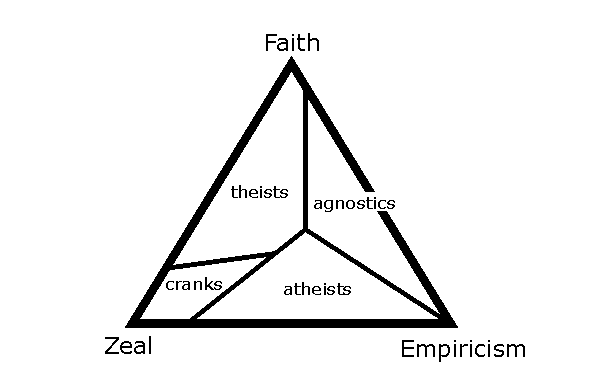

Because of this, I think a third factor needs to be considered, which for want of a better word I’m referring to as ‘zeal’ (I also considered ‘passion’, which might be a less inflammatory choice). This is a measure of commitment to a particular worldview; how much do you care about it being true? Does it bother you that others don’t share it? Inspired by a recent treatise on ‘thermopienamics’, I’ve tried to map different theological outlooks onto a ternary diagram, with Empiricism, Faith and Zeal as the vertices. The advantage of this representation is that it (hopefully) emphasises that I’m not talking about absolute quantities here, but a relative measure of which attributes most control someone’s positioning in the theological menagerie: someone who plots near the faith vertex is not necessarily antiscientific per se, it is just that faith is far more important to them than empiricism.

In this representation, the Faith/Empiricism side of the triangle is dominated by agnosticism, because they generally don’t particularly care one way or the other about such matters (or at least aren’t too bothered by others disagreeing with them). The boundary between the theist and agnostic sectors reflects the fact that people who are more passionate about their religion can maintain their faith even when they have an appreciable regard for science and empirical reason, whereas less passionate theists are more likely to drift into agnosticism. Likewise, if you tend toward empiricism, the more you care about the existence or non-existence of God(s), the more likely you are to drift over into the realm of the actively disbelieving atheist. I’ve reserved the high end of the zeal realm for cranks and conspiracy theorists, whose passion is tempered by neither faith nor empiricism.

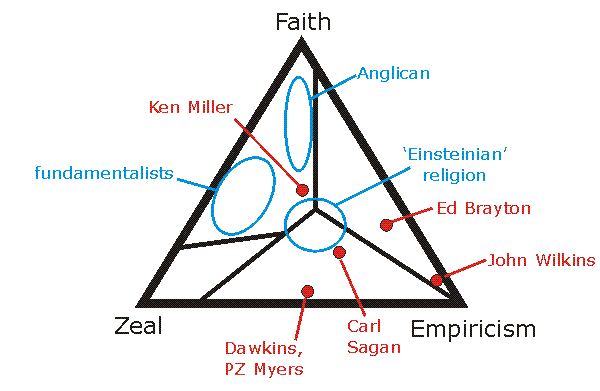

In the next figure, I’ve tried to plot the positions of significant religious denominations and the major players in the recent spat (apologies to anyone who feels misrepresented).

Does this help us any? In my mind, it gives us a new perspective on some recurring problems. For example, the suspicion moderate agnostics seem to have of some of their atheist brethren can be understood to stem from their suspicion of too much zeal for any particular worldview; they feel it is divisive and polarizing. Both fundamentalist theists and the more vocal atheists lie in the same direction in this regard, even though the focus of their zeal is entirely different. This confusion between faith and passion may also be behind the theists’ “atheism is a religious belief too” argument.

Likewise, the snide remarks which sometimes get directed towards “timid” agnostics by atheists also reflects a misunderstanding – if you don’t personally find the existence (or not) of God particularly important, you are probably happy to stick to the more technically correct position with regard to non-corporeal entities that exist outside of space and time: “there almost certainly is no God, but we can never be 100% certain”, to adapt Dawkins slightly. The mainstream Anglican Church - which places great value on thoughtful, less boisterous faith, and is looked on with some contempt by the evangelical wing for just that reason - is more than happy to stick God into that gap, which science may make smaller but can never completely close (listen to the Archbishop of Canterbury talking to John Humphrys, for example). This is as close as you get to the ‘non-overlapping magisteria’ idea in the real world: there is still some overlap, but in practical terms it is very small, and allows people (if they wish) to reconcile their faith with the empirical world. This includes people like Ken Miller (who is, of course a Catholic, but the idea is the same). In contrast, for fundamentalists the magisteria overlap almost completely; because they regard revelation and scripture much more highly than science, in their minds science loses and is denied.

Another interesting feature of this representation is that it suggests that the more zealous theists, if something causes them to doubt their faith, may be more likely to move directly into the atheist camp without any intermediate stops in agnosticism. I think this is interesting in light of the widespread anger amongst the “deconverted” which surprised Dawkins so much on his recent US tour. Perhaps the more zealous Christians are more likely to feel betrayed or lied to if they lose their faith than the former Anglicans who Dawkins would more commonly encounter in the UK, which makes them a bit more passionate in their atheism. And, somewhat heretically, it might suggest that atheists can have a uniquely effective role in the conversation – in supporting and encouraging these refugees.

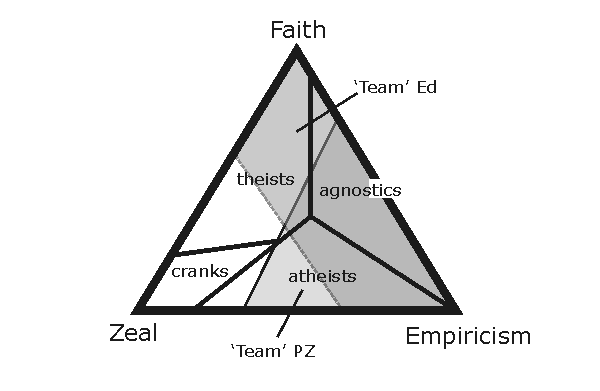

The other sector I’ve tentatively identified in the middle of the triangle is the realm of the ‘Einsteinian religion’ which Dawkins discusses in The God Delusion - where effectively, ‘God’ is the universe revealed by science, capable of inspiring wonder and awe but not so keen on the smiting or prying into peoples’ personal lives. I’m wondering if this is the true middle ground we should be aiming for – the triple point of the theological system. But for now, if you’re picking sides, by my reckoning I’m fairly sure that a lot of us can pick both (Update: i.e., this whole notion of "teams" is meaningless, there is just a slight difference in the theological outlooks that people are comfortable with - in this particular case I see Ed as uncomfortable with the overly zealous, and PZ as uncomfortable with the overly credulous):

All we need to do is get the moderates to see that a little bit of passion is not always a bad thing, and perhaps get the hardcore atheists to concede that people are always going to believe silly things, but some silly things are more harmful than others, and then we can all be one big happy creationist-bashing family again. Until Christmas, anyway.

30 November, 2006

Phases of belief

Posted by

Chris R

at

12:16 am

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

6 comments:

From your diagram, it would seem that any ternary composition should eventually end up at the "Einsteinian religion" eutectic.

Barring, of course, kinetic factors. I can't imagine the amount of time it would take for Dawkins or PZ to over come that barrier!

Hi PZ - That was my point, really; that there are no teams at all, just different (but largely overlapping) comfort zones. Hence the quotes. Perhaps it should be "team" x rather than "team x".

This is kind of similar to the Worldview Quiz, although I think that that grades religion more finely than science...

Hmmm. I'd say there's also another issue entangled with "Zeal", which is "perceived threat". Some but not all zealous types will consider all "non-believers" as threats, but they won't necessarily respect that triad -- indeed, their greatest fear/hostility will commonly be for the close variants (heretics/schismatics) of their own "creed".

This isn't really symmetrical, but even those who aren't particularly committed to their position on the theism/empiricism edge, may feel threatened by "excessive" zeal, even from those who almost agree with them.

A few thoughts:

There was a book out recently- reviewed in Eos about a year ago, that demonstrates that science is a faith-based activity- that there are certain fundamental tenets that we all assume in order to accomplish anything. Unfortunately, I don't recall the details.

Second, of the three end-members, empiricism is the most expensive. I had a chat the other night with one of our post-docs. He was telling me how good it was to work in modelling, where all you need is a supercomputer account and salary- no lab to manage, techos to supervise, or associated bullshit (OSHA, consumables, HR, etc). So funding cuts tend to push people to the left.

Finally, the lower left-hand corner looks like a pretty scary place.

The point about "perceived threat" is a good one. I think this depends on the size of your comfort zone, or the amount of deviation from your own position you are willing to tolerate; I suspect it is quite small towards the left hand side of the triangle. This is indeed a scary place, but more scary is that people exist who inhabit it...

Post a Comment